A Greco-Roman Look at Sanskrit Theater

By Roberto Morales-Harley

Comparing Theaters

Any well-read person who has had the pleasure to read both Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex and Kālidāsa’s Śakuntalā will probably know that the differences between the two far surpass their similarities. The Greek tragedy begins with a deathly plague, progresses through several ominous oracles, and touches on themes like murder, suicide and self-injury, only to wrap things up with a protagonist defeated at the hands of fate, as well as an audience likely pitying him and fearing suchlike disgrace. The Sanskrit nāṭaka, on the other hand, covers such a wide range of topics as the idyllic life of hermitages, the ludicrous nature of buffoons, the power of curses, the ways in which bad and good luck can tilt the scales, and the relationship between gods and men, all this while both characters and spectators ride along in an emotional roller-coaster, encompassing not only the joy of a love story, but also the didactics of genealogy. Apples and oranges.

It is also likely that not many people will know the complexity of each of these theatrical traditions. Besides Tragedy, Greek theater has Comedy. But more importantly, even the Greeks were not as dualistic as often thought of, since they also developed a third subgenre in the form of Satyr Drama. In Rome, the scene is still more intricate, since tragedy is not viewed as monolith but treated separately as either Fabula Crepidata or Fabula Praetexta, and likewise, comedy manifests itself in the forms of Fabula Palliata, Fabula Togata, Fabula Atellana, and Mimus. India is no exception, given the fact that there are as many as ten main forms of theater: Nāṭaka and Prakaraṇa, but also tragic-like subgenres like Aṅka; comic-like subgenres like Prahasana, Bhāṇa, and Vīthī; and even heroic-like subgenres like Samavakāra, Īhāmṛga, Ḍima, and Vyāyoga. Some mix and match between all this can at least allow us to compare varieties of apples.

The Greek Influence Hypothesis

In 1852, Albrecht Weber first formulated what then came to be known as the “Greek Influence Hypothesis”. According to him, (a) we have no preserved early Sanskrit plays, but (b) we have testimonies of Greek plays being represented in Bactria and in North- and West India; therefore, (c) it is possible to presuppose a Greek influence in the origins of Sanskrit theater, even though (d) there seems to be no specific manifestations of such general influence.

Since Weber, new developments allow us to rethink these four statements. (A) In 1906, Ganapati Shastri discovered thirteen Sanskrit plays and attributed them to the early playwright Bhāsa. (B) In 1975, Paul Bernard discovered a building that used to function as a Greek theater in the region. (C) Greco-Roman influences in Sanskrit romance, fable, and epic have been argued for, respectively, in 1940 by Vittore Pisani, in 1987 by Francisco Rodríguez Adrados, and in 2008 by Fernando Wulff Alonso. If influences happened not only in theater but also in other literary genres, we could move on from considering it a mere possibility and start talking about a highly probable practice. (D) Lastly, specific borrowings from Roman theater into Sanskrit theater were suggested in 2012 also by Francisco Rodríguez Adrados.

When comparing some Greco-Roman texts to some of the Sanskrit plays attributed to Bhāsa, the parallelisms are shockingly detailed: paintings being described in words, intentional avoidance of death and violence on stage, merging of two plots into one. I believe that any Indologist who reads this short list would without a doubt be reminded of Sanskrit theater. But I assure you that the same would happen for a Classicist thinking of Greek or Roman theater! Could this be more than a series of lucky coincidences?

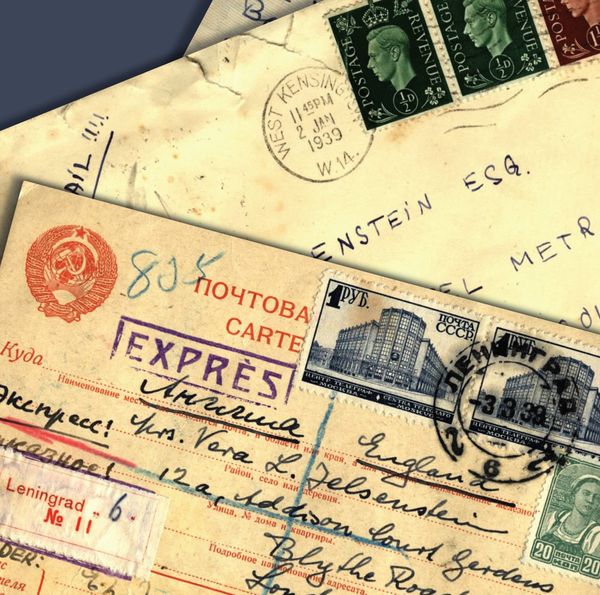

The Embassy, the Ambush, and the Ogre

The book The Embassy, the Ambush, and the Ogre: Greco-Roman Influence in Sanskrit Theater tackles an issue that, although first raised nearly two centuries ago, still had not received a full-length treatment in the form of a monograph. The study is based on three literary motifs: the embassies from Iliad 9, Mahābhārata 5, Euripides’ Phoenix, and (Ps.-)Bhāsa’s The Embassy; the ambushes from Iliad 10, Mahābhārata 4, Ps.-Euripides’ Rhesus, and (Ps.-)Bhāsa’s The Five Nights; and the ogres from Odyssey 9, Mahābhārata 1, Euripides’ Cyclops, and (Ps.-)Bhāsa’s The Middle One. But the comparisons do not end there. Other plays by the Greek playwright Aeschylus or by the Roman playwrights Plautus and Terence are also compared here for the first time with some works of Sanskrit theater. Hopefully a study like this will start a long-overdue conversation between Classicists and Indologists about these subjects.

Access The Embassey, The Ambush, and the Ogre for free at: https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0417