Africa’s Image in Ghana’s Press: The influences of global news organisations

by Michael Serwornoo

I have done very little in my entire life except to follow, practice and teach journalism. From my early days in the practice of journalism until today, many things remain clear and incontestable to me and yet these same things are the subject of massive global debates. I will give you one example. Our news (ATL FM news) on the hour captures but a figment of the struggles and triumphs of the people of Cape Coast, the first capital city of Ghana. It is clear to me that we could not and we will never individually or together with all media houses capture the true image of the people of Cape Coast in our broadcast or printed pages or social media posts. Several reasons account for this.

First, journalists are guided fundamentally by mechanistic rules that knowingly or unknowingly evade what we call objective selection of the top events of the day which we will either write about or speak about. Second, beyond these mechanistic rules of journalism, other very important criteria relating to ownership, society and cultural milieu in which we operate significantly influence further selection. It is just impossible to see the news of the day as an objective assessment of the day’s events. Journalists and media practitioners who make such objective claims are just idealistically untrue to themselves.

As journalists, we are involved in a very special translation of events into stories. We attempt to render events visibly to our audiences to the best of our knowledge. This translation hardly accommodates the pre-event circumstances which significantly determine why the events are occurring and with which severity. Our translations, with their weaknesses, are received by the audiences from a different lens. The reception process is something we cannot control but we can also not refute to have influenced it with our choice of words and images. In the nutshell, we are involved in a complicate practice that is far from been described as our objective assessment of the day.

But when it comes to Africa and her predominantly negative reportage around the world, a debate ensues which makes useless my previous understanding of the journalism practice. How could it be that the global journalists’ reliance on objective reportage of cultural milieus exonerates them from such complex journalistic translations I have explained? In any case, their form of translation is even more complex because they are highly incapable of understanding what they see because of the newness to the new culture. Why have we found pleasure in casting doubts about previous and continuous empirical evidence that continues to be adduced against the leading global press and their visible negative agenda? Could it be that representation in itself remains flawed as a concept and more so evident when one culture takes the centre stage in describing other cultures? Erik Bleich and his colleagues, earlier this year, have published research that has answered the empiricist calls. In fact, I was not surprised because I found several calls for empirical evidence far-fetched and I evaluated such calls as a form of rationalisation that promotes the establishment of a world order. A world order that keeps Africa under-reported and even the few reported stories must continue to be negative.

The Africa rising discourse leads a new wave of optimism about the continent’s image in the Northern press. A few books dealing with this topic over the years remain insightful, to a certain extent, but they equally created a gap by concentrating their empirical research largely on Western media.

In this book, I answer the question of how Africa’s so-called improved image has been mirrored around the world, particularly in one important country on the continent itself. First, a theoretical synergy that accounts for all the elements that make up the foreign news selection process. Second, analysing the African press to demonstrate the gravity of the rippling effects of centuries of Afro-pessimistic international communication order and ambivalences it has created when it comes to the continent’s reportage. I used Ghana as a case for the exploration of these topics. Third, accounting for details through a methodological fluidity with applications of Spradley’s ethnographic interview and David Altheide’s ethnographic content analysis (ECA) have cleared my doubts that empirical flaws have accounted for previous research that concluded that Africa was negatively reported.

I have demonstrated in this book that Africa’s media image in Ghana is dominated by themes of war, crime, killings, crises, and terrorism. The African story is narrated with a negative tone and with significant reliance on global news organisations from the Northern hemisphere as sources. For the Ghanaian journalists and editors, harsh economic conditions and their cost-cutting rationale in the media business, plus proximity in journalistic ideology and the uneven power encounter in the colonial experience have aggravated the kind of coverage Africa gets even from her own continent.

You can find out more about the book here.

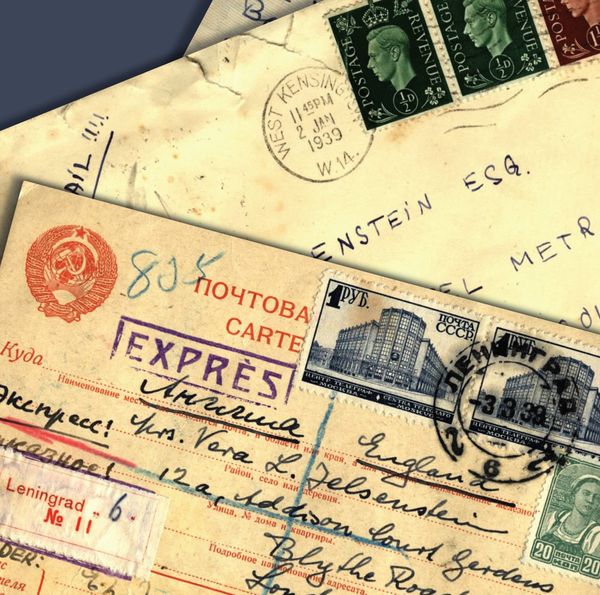

Photo by Bank Phrom on Unsplash