Changing the conversation around Existential Risk

by Dr SJ Beard

The Centre for the Study of Existential Risk was established in 2014 at the University of Cambridge. I was one of its first postdoctoral researchers, starting in 2016, and when I joined the first question anyone used to ask me was “what is an existential risk? And has it got anything to do with Jean Paul Sartre?” “No”, I would reply, “existential risk refers to the risk of human extinction and global civilization collapse!” at which point they would usually give me a very strange look and try to change the topic of conversation.

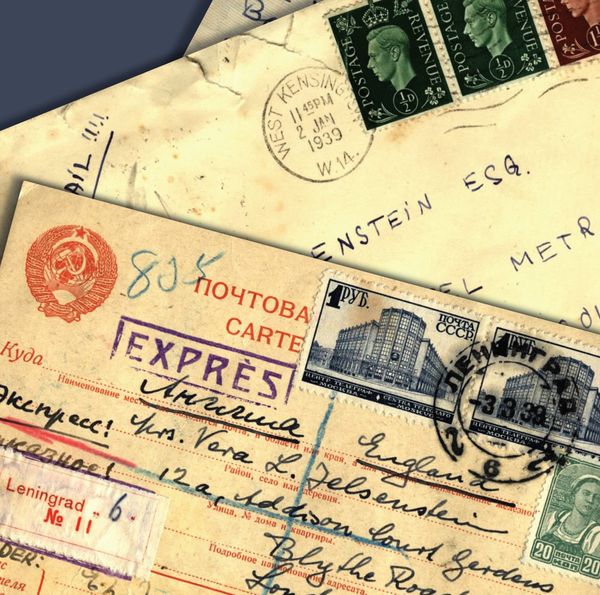

Fast forward 7 years and those conversations are nothing but a distant memory. Speak to anyone, from journalists and politicians to participants at my weekly dance classes and they not only tend to already know what existential risk is but are glad to hear that there are people like me and my colleagues studying it. The last 7 years have been an utter roller-coaster, from rising panic about climate change and the lightning pace of developments in AI and biotech, to explosive nuclear tensions following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and of course our personal experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic, a global disaster far less dangerous than those we worry about at the Centre but that has left 8-billion humans feeling battered and bruised nonetheless.

Yet, even though talk about existential risk now appears to be everywhere, so many people are left with no idea how it relates to them and what they can do about it. That is where The Era of Global Risk comes in. Me and my colleagues have spent years working to understand this most worrying of risks but we are academic researchers who spend most of our time talking to other academics or technical experts across government and industry. So, we set out to write about some of the key findings of our research and to make this accessible to a broader audience in the hope that others could share in, and engage with, our work.

The resulting volume does not aim to alarm or incite; the essays are rich in detail and draw upon a huge volume of research. They are written for any educated reader who wants to know more about Existential Risk Studies, the emerging transdisciplinary field of research that has sprung up at CSER and elsewhere. The first half of the book looks at different aspects of this field: its history and development; the methods it uses to model systemic collapse; it’s approaches to governing science and technology; its relationship with global justice; and its need to diversify and become more inclusive if it is to succeed. The second half then draws upon the results of this field to survey the main drivers of existential risk: natural phenomena like asteroids and volcanoes; anthropogenic climate change; biotechnology; AI; and nuclear weapons. Through it all the authors pose a single question, how can we move beyond recognizing the danger we are in to understand how to actually reduce that danger – to move beyond our present era of global risk to one of global safety?

For instance, a common theme running through many chapters is the need to distinguish between existential risk and existential threats. Often, when we worry about the worst things that could happen to humanity our minds are drawn to individual catastrophic events, like an asteroid strike or nuclear war, and we imagine that the only way of safeguarding our future is to make sure such events never happen. However, this is only half the story. We are not only in danger because these threats exist but also because we are vulnerable to them. This vulnerability can take many forms, from the global infrastructure pinch points that might be destroyed by even a relatively small volcanic eruption or tsunami, to the lack of preparedness for major disruptions to the earth’s food system, to societal fragilities that make us more likely to fracture and fight than to unite and flourish. But these vulnerabilities are not just another thing to worry about, they also show us how we can build greater resilience and risk preparedness that could make even worse case scenarios less bad than they would otherwise be.

By identifying such opportunities for risk mitigation, in all its forms, and working out how to harness them in ways that are just and beneficial for society as a whole, we hope to stimulate a further transformation in the conversations that researchers like me are having. Where once we were met with incomprehension and guardedness (“this sounds strange”) and now we are rewarded with recognition and encouragement (“this seems important”) we hope that in the future our work can be embraced with understanding and collaboration (“I want to be part of this”).

This is an Open Access title available to read and download for free or to purchase in all available print and ebook formats below.