Destins de femmes: French Women Writers, 1750-1850

by John Claiborne Isbell

Who gets to speak and who does not? One fine day in 1950-something, the Comtesse de Pange, President of the Société staëlienne, put on her best and went to meet the head of the Pléiade, that gatekeeper of the French literary canon, only to be told that Staël would never appear in their series. Well, now she has. But constructing this anthology of French women writers, 1750-1850, still involved consulting more than one worn Second Empire edition: perhaps half its thirty women authors have barely been republished since 1900. What is going on?

A sample of thirty leading male authors, 1750-1850, would not encounter this difficulty. Several – Rousseau, Voltaire, Diderot, Chateaubriand, Musset, Hugo – have earned handsome complete works, and journals and societies proliferate. But the powers that be, it seems reasonable to say, which after 1793 banned the word citoyenne and women wearing trousers, have by and large been more comfortable sending Frenchwomen to the guillotine than seeing what they had to write. In French, femme publique and homme public mean two different things.

Aux grand hommes la patrie reconnaissante, “To great men the thankful fatherland,” reads the inscription above the Panthéon in Paris. The building contains just six women, with Marie Curie, who won her two Nobel Prizes in 1903 and 1911, entering only in 1995. The French establishment, like others, has evidently preferred celebrating predominantly male achievement, and the patriarchy that complicated our thirty women’s lives – from works left in manuscript to beheading – has been remarkably at ease erasing them from its national narrative.

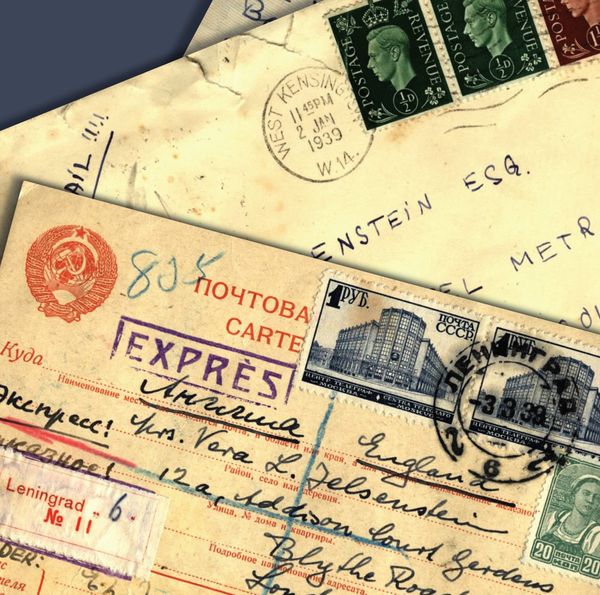

It seems time, in short, for a new century of French women’s voices. These women range from duchesses to butcher’s daughters, from royalists like Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun to socialists like Flora Tristan. Confronting the Revolution, they span the political spectrum from left to right, as their publishing choices here stretch from resolutely public work – Olympe de Gouges’s ringing Déclaration des droits de la femme, in 1791 – to private memoirs and correspondence, even personal diaries like Louise Colet’s Mementos. The anthology includes love letters – Juliette Drouet – and philosophy – Sophie de Condorcet, and its authors range from Suzanne Necker, who condemned divorce in 1794, to Flora Tristan, shot in the chest by the husband she could not be free of. From this diversity, in turn, a fascinating narrative emerges, one of women’s multiple responses to patriarchy’s dead hand. Certain themes recur – wet nurse, convent, unhappy marriage – as do certain decisions – a focus, for instance, on ‘female’ genres, like Sophie Cottin who published anonymous novels and left her poetry unpublished, or like the great memoirists of Revolution and Empire – Lucie de La Tour du Pin, Sophie de Rémusat, Adèle de Boigne. And yet, more than one woman defied that male pressure to swim against the current, like Sophie de Condorcet adding her own eight letters to her translation of Adam Smith, or Marceline Desbordes-Valmore giving up acting for a career as a major, though still-understudied, Romantic poet; like Marie Jeanne Riccoboni or Sophie Gay writing theater; like Germaine de Staël, Olympe de Gouges, or Flora Tristan writing and publishing politics.

1750-1850 is the Romantic period writ large, and this anthology was born out of the insight that French Romantic historiography remains conspicuously lopsided. Aside from George Sand and Germaine de Staël, women writers are often name-checked at best, if not passed over in silence, including figures like Félicité de Genlis, who published over 140 books and educated Louis-Philippe. The women of the age deserve better of posterity; frankly, they deserve better of France. My hope is that this anthology of women’s destinies will encourage scholars to reopen those old Second Empire volumes, as I have, and maybe bring out a new edition; to speak of Sophie Cottin at a Nineteenth-Century French Studies conference, instead of feminism in, say, Flaubert (who trashed Louise Colet) or the misogynist Baudelaire; to ask, finally, whether French Romanticism has a missing planet, one raising questions less urgent to its male practitioners. Victor Hugo told Juliette Drouet that she was not to leave her apartment without him, and the two stayed that way for fifty years. Today, the splendid French National Library files Drouet’s letters not under D, for Drouet, but under H.

This is an Open Access title available to read and download for free or to purchase in all available print and ebook formats below.