From Handwriting to Footprinting : Text and Heritage in the Age of Climate Crisis

Anne Baillot - June 2023

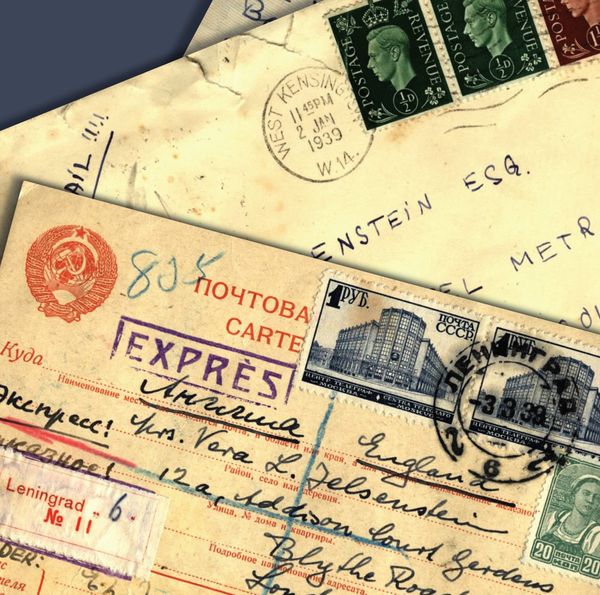

What should you do if you found old papers in the drawer of a family home and want them to be preserved and made available for further consultation? - You can bring them to the local archives, but public archives have relevance criteria that family papers do not always fulfill. Alternatively, you can take a picture of the old papers and put the pictures online. But how sustainable and accessible will this online archive that you set up on your own really be? From Handwriting to Footprinting explores the options that are available in such a situation as well as their technical feasibility. It serves as an example throughout the book in which a variety of approaches to text and heritage are discussed, together with what they tell us about our relationship to the past.

Private archives are one of the case studies in an encompassing argument that strives to reconcile the preservation of the past, access to text, and a frugal use of natural resources. This argument builds on archival theories and the history of the book, but also on digital media studies, and the nascent domain of the assessment of environmental impact.

Archival theories are presented in Chapter 1, where they help draw a parallel between the techniques of analog archiving and those of digital archiving. In this chapter, I show that we have means to preserve documents from the past in a manner that accounts for the fact that preservation is ultimately always selective. The creation of a literary text is exemplary of this phenomenon: not every draft of every text can be kept, and material is always preserved in a fragmentary manner. We have to accept that some elements of our heritage that may seem of crucial importance at some point in history lose their relevance over time, while documents initially deemed irrelevant reveal their importance later on, when it is too late to retrieve them. Scholars are now struggling to find and identify texts written by women in the 18th and 19th century, for instance. Preservation choices engage a society’s vision of its past and inevitably contribute to defining that of its future generations.

Textual heritage is not only kept in archives, it is also stored by libraries in the case of printed material. Publications stand in the focus of Chapter 2, together with those actors who are instrumental to them. In particular, the relationship between publisher and author plays a key role in order to understand the shape in which textual heritage is published and transmitted across time. A look at the correspondences between Goethe and his publishers and at the way in which Ludwig Tieck treated his shows how complex it is for authors to find a balance between trusting a publisher, asserting authorship, and addressing financial needs. Ultimately, this also defines the way in which literary texts reach their readers.

For readers, digital media add further complexity to the way in which text can be accessed. While we are still trapped today in our habit of thinking of text in the page format, digital media provide the opportunity to rethink not only the way we read on a daily basis, but also the way we preserve and access heritage material. I close this chapter by listing quality criteria for digital text that show how to reconcile the ideals of universal dissemination with existing technical developments.

Not all technical improvements are synonym of unequivocal progress, though. In Chapter 3, I engage in a critical consideration of the environmental impact of digital archiving and publication practices. I argue that setting up a private digital archive of your family papers is by far not the best solution from an ecological perspective, as it has a significant environmental impact and relies on technologies that are not easily shareable and reusable. I discuss digital methods that provide access to textual heritage and are considered exemplary today taking into account their environmental footprint. It appears that the material made available online is, in fact, not at all as universally accessible as it may initially seem. What is more, availability schemes are more impactful than what could be hoped for. So, what can and should be done if attempting to provide access to text ultimately deprives lesser resourced readers of any access, be it because their internet connection is not good enough, or because the energy used to cool north-western datacenters and library storerooms comes at the expense of catastrophic living conditions in the Global South?

The final pages of the book explore solutions to resolve this contradiction. I address what needs to be considered when measuring the environmental impact of access to text. Ultimately, I argue for reducing environmental impact to a level where the preservation of cultural heritage and natural resources can be compatible. I show that strategies to achieve this goal can be developed and implemented by heritage professionals and scholars. However, given the accelerating climate and diversity crises, there is no time to lose.

This is an Open Access title available to read and download for free or to purchase in all available print and ebook formats below.