How do languages die? The case of the Jewish Arabic dialect of Gabes (Southern Tunisia)

By Wiktor Gębski

According to official statistics, a language dies approximately every 40 days. The critical situation of language diversity worldwide is worsened by globalization and advancing climate change. Although Arabic may not be perceived as an endangered language by many, some of its varieties are expected to vanish within the next two decades. The Jewish dialects of Arabic are predicted to disappear within the next few years and are among the most endangered within the Semitic family, along with Neo-Aramaic.

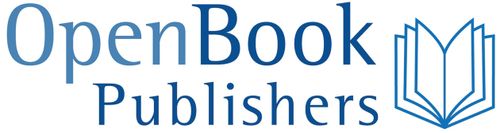

The Jewish communities of North Africa have a rich and extensive history spanning over two millennia. From Morocco to Libya, these communities thrived within the vibrant fabric of North African society, leaving behind a distinct linguistic legacy in the region. Jewish dialects of North Africa, believed to have originated during the initial wave of Arabization in the 7th century, represent the earliest strata of Arabic in the area. Formed through a blend of Arabic, Hebrew, Berber, and French, these dialects reflect the diverse heritage of the communities that gave rise to them.

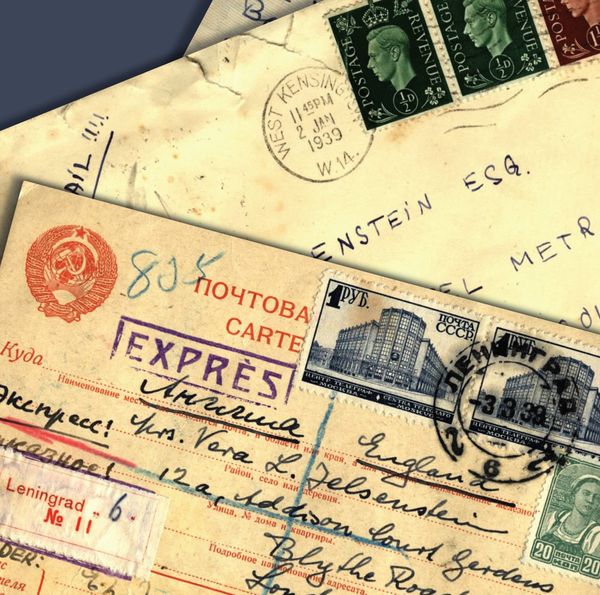

However, in the 20th century, there was a significant migration of Jews from Arab lands to Israel. This migration occurred primarily due to a combination of factors, including the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, rising anti-Semitic sentiment in Arab countries, and political instability in the region. Following Israel's independence, many Jews faced persecution, discrimination, and violence, prompting them to leave their homes and seek refuge in Israel. This mass migration resulted in the resettlement of hundreds of thousands of Mizrahi Jews in Israel, where they contributed to the cultural, social, and economic fabric of the newly formed nation.

In addition to the political and social factors driving the migration of Jews from Arab lands to Israel in the 20th century, there was also a significant loss of their vernacular languages. As these communities resettled in Israel, many of them faced pressure to assimilate and adopt Hebrew as their primary language. Consequently, the vibrant and diverse Jewish dialects of Arabic, spoken for generations in countries like Morocco, Iraq, Yemen, and Tunisia, began to decline rapidly. This loss of vernaculars represents a poignant aspect of the migration experience, as it severed ties to cultural heritage and linguistic traditions that had been integral to Mizrahi Jewish identity for centuries. Despite efforts to preserve these languages and revitalize their use within the community, the shift towards Hebrew as the dominant language has contributed to the gradual disappearance of these unique linguistic heritages.

The Jewish varieties of Arabic exhibit several differences from their Muslim counterparts. As early as the 20th century, linguists like Marcel Cohen recognized the scholarly value of these Jewish dialects and conducted studies to document them and explore their distinctive features. My volume focuses on documenting the critically endangered Jewish dialect of Arabic once spoken in Gabes, Southern Tunisia. Gabes, alongside Tunis and Djerba, was one of the most important centres of Jewish life in Tunisia, with the Jewish community of Gabes being one of the oldest in the country. Currently, only a handful of native speakers remain, while their children and grandchildren have limited knowledge of Jewish Gabes or do not speak it at all. Drawing from several years of fieldwork in Israel and France, the book delves into the grammatical structure of this dialect and seeks to elucidate its typological relationship with other Jewish and Muslim dialects in the region.

The volume is structured into three main sections: phonology (Part I), morphology (Part II), and syntax (Part III). While the first two sections adhere to a traditional grammatical model, syntax is approached from historical and cross-linguistic perspectives. Chapter 2, dedicated to phonology, is broadly divided into two subsections: an analysis of the sound inventory and phonotactics, which includes a description of syllable structure and epenthesis patterns. The morphology section comprises Chapter 3, which covers verbal morphology, and Chapter 4, addressing nominal morphology, including pronominal forms. Lastly, the syntax section (Chapters 5–7) encompasses various subsections exploring syntactic phenomena such as definiteness, genitive constructions, grammatical agreement, subordination, expressions of tense and aspect, syntax and pronouns, and sentence typology. This linguistic study underscores the differences between the Jewish dialect of Gabes and its Muslim counterpart. While the former exhibits features typical of sedentary, first-layer dialects, the latter could be classified as a Bedouin-type dialect. Moreover, the examination of the tense and aspect system suggests that Jewish Gabes, like other Jewish dialects of North African Arabic, features a distribution of the active participle that sets them apart from the Muslim dialects. The grammar is complemented by an appendix containing a corpus of selected folktales cited in earlier sections of the volume.

The destiny of Jewish Gabes and other Jewish dialects of Arabic is sealed—they will all cease to be spoken within the next several years. Therefore, it is crucial to embark on comprehensive fieldwork and systematically record the language while reliable speakers are still available. The study of Jewish Arabic varieties is essential for understanding the social networks of the Middle East and North Africa that these dialects reflect. Their loss represents not only the disappearance of linguistic diversity but also the erasure of centuries of cultural heritage, identity, and coexistence between Jewish and Muslim communities.

This is an Open Access title available to read and download for free or to purchase in all available print and ebook formats below.