Life writing, family stories and ‘history from below’

By Alison Twells

A Place of Dreams has been many years in the making, the long gestation quite simply because it took me so long to work out what kind of book it should, or could, be.

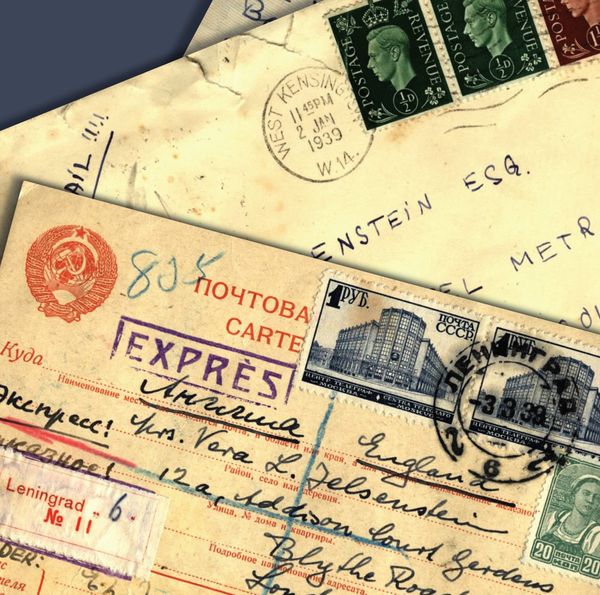

The book explores the wartime coming-of-age of Norah Hodgkinson, a working-class schoolgirl from the East Midlands. It is crafted from a ‘suitcase archive’ containing 71 pocket diaries, which Norah began writing in 1938, when she was 12 years old. Alongside the diaries was a collection of letters from a sailor who—it turned out—had received a pair of socks Norah had knitted for the Royal Navy Comforts Fund in 1940, and a stash of photographs of him—I’ve called him Jim—and his brother—Danny—who was in the RAF and with whom Norah fell in love.

Piecing together Jim’s letters and Norah’s diary entries, it soon became clear that these were not the kind of men you’d want writing to your fifteen-year-old daughter. But Norah, coming of age in a period in which finding love and romance was the pinnacle of female achievement, was utterly thrilled by her entry into this new grown-up and very modern world.

Norah’s diaries are unique. Despite over sixty years of ‘history from below’, we still have so few accounts of ordinary peoples’ lives told in their own voices and on their own terms. Evidence written by working-class people is more likely to end up in a house clearance skip than an archive. Working-class girls are surely among the most under-represented in history. We have plenty written about them, material which often represents them as a problem in some way. In Norah’s era, we see newspaper articles shrieking fears about the alleged lax morality of girls and young women during the war, and commentaries of social workers, journalists, reformers, the police, the records of juvenile court proceedings and government departments, the concerns of which are usually very far from the girls’ own. As the daughter of a postman and a former domestic servant, might Norah’s diaries allow a different kind of access to a working-class girl’s interior life?

As well as unravelling Norah’s wartime experience, A Place of Dreams asks: what kind of writing would best allow me to tell Norah’s story?

Norah’s diaries are a challenge to read. It is not simply that much of what she wrote about was very mundane. Her daily concerns—the weather, her routines and household chores, the comings and goings of family and friends, her health, love interests and occasional world events—were all shared with other diarists, like the middle-class women who wrote for Mass Observation during the war. But Norah’s diary entries—written in tiny squares that allow for no more than twenty words a day—are more akin to almanacs and pocketbooks than the discursive, introspective diaries that find their way to publication. Laconic and telegraphic, they have little in the way of plot, dramatic tension, character development or self-reflection. Her use of parataxis, the juxtaposition of unrelated daily events, accord the ordinary and extraordinary equal value within any given daily window. The personal pronoun, the ‘I’, is almost entirely absent. Full sentences too. Norah relies on phrases composed of verb/object pairings (‘wrote to Danny’), with an occasional adjective thrown in (‘beautiful letter from my love’). Her style is so terse as to seem almost coded, her disjointed, staccato sentences hard to decipher without insider knowledge.

Given my training, the obvious way forward would be to write about Norah’s diaries, academic-style. Academic historians have much to commend us. We know our sources: their strengths and shortcomings, how they came into being, what they might mean. We are good at probing beneath the surface, steering clear of simplicity, unsettling false certainties. But putting Norah’s archive through the academic mill, subjecting her daily entries to an outside telling, would not get close to her life as she lived it. It could not bring her diaries to life. Nor would it lead to a story that Norah would recognise as her own, or even want to read.

A Place of Dreams builds on long-standing criticisms of academic writing; criticisms which say that our commitment to detachment and distance, to the solemn, argumentative voice of a purportedly neutral ‘hidden narrator’, doesn’t actually do what we claim it does. I ask if story can carry interpretation, if family stories and methods drawn from life writing might allow the kind of ‘insider’ perspective that Norah’s diaries feel to me to need, and if I can do all of this and still call it history…

‘History from below’, I have come to believe, requires more than a focus on an ordinary life written in an academic voice. It requires attention to both form and voice: an exploration of forms that allow other ways of knowing – through family stories and imagination, perhaps; and a writerly presence that is transparent, honest and warm.

For girls as a problem, see Carol Dyhouse, ‘Was There Ever a Time when Girls Weren't in Trouble?’, Women's History Review, 23:2 (2014), 272-274.

For criticism of academic writing, see: Alison Twells, Will Pooley, Matt Houlbrook and Helen Rogers, ‘Undisciplined History: Creative Methods and Academic Practice’, History Workshop Journal, 96:1 (2023), 153-175, and references therein.

For family stories as ‘inside history’, see Alison Light, Common People: The History of An English Family (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2014).

Read A Place of Dreams: Desire, Deception and a Wartime Coming of Age by Alison Twells freely online or buy a copy on our website.