Looking forward, looking back: William Moorcroft in the news

By Jonathan Mallinson

Within the space of just five days in June this year, William Moorcroft was twice in the news. One item recorded the sale at auction (for a record-breaking price) of a particularly rare example of his ceramic art. The other reported the rescue from liquidation and the return to family ownership of his pottery works in Burslem.

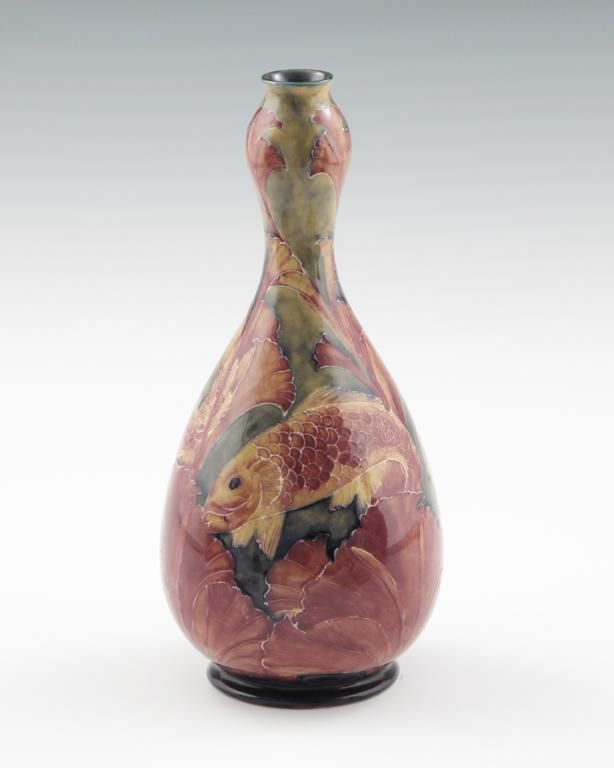

The vase, in double gourd form, is decorated with carp, swimming through reeds in an eye-catching palette of red and ochre. The object is indeed rare; only three others, similar but not identical, are known to exist. Its significance, though, derives not just from its rarity or its current market value, but from the circumstances of its creation.

It dates to 1914, the year following Moorcroft’s move to his own works from J Macintyre & Co, where he had been employed as Head of Ornamental Pottery since 1897. This was a turning point in his career, the outcome of increasingly tense relations with the firm’s General Manager which had resulted in the closure of his department. It was a moment of liberation, the opportunity to create pottery entirely on his own terms, with the small devoted team of co-workers (as he called them) which followed him from Macintyre’s. Designed and built in less than six months of intense activity, these new works were the mark of his determination and self-belief, clearly seconded by Liberty’s who co-funded the project.

What more appropriate motif to capture the import of this moment than that of the carp, symbol of perseverance and courage, whose arduous journey up the Yellow River to a famed waterfall cascading down from the Dragon’s Gate was the stuff of Chinese legend. Any carp strong or brave enough to make a final leap over the waterfall would be transformed into a dragon, but such an exploit was rare.

Moorcroft’s vase recalls high points in his earlier career. The carp motif featured in a limited series of vessels made at the turn of the century, when his innovative Florian ware was generating exceptional critical acclaim; and its distinctively rich palette characterised some of his last (and most successful) designs at Macintyre’s. But there is nothing celebratory about this pot, for all that Moorcroft’s move to Burslem represented a remarkable triumph over adversity. It depicts carp, after all, not a dragon; it suggests a journey, not a parade. And this is not surprising for an artist who already, in his professional and personal life, had experienced multiple challenges and setbacks. And more were to come. His first year at Burslem was beset by practical problems of different kinds; and others, global and uncontrollable, were on the horizon, extending unforeseeably far into the future. But for Moorcroft, challenge was creative, adversity was there to be overcome. As he wrote to his daughter on 17 October 1930, just short of a year after the Wall Street crash: ‘I feel that difficult times are with us, to force the best out of us. We do better work when we are faced with something to fight against’. This pot is characteristic of that creative response, a profession of faith, a statement of intent to turn adversity into art.

It is an exceptional vase in many ways, but it offers, too, a broader insight into Moorcroft’s vocation as a potter. Evidently not made for commercial production, this evocative object was, nevertheless, sold (or gifted), reputedly acquired by its first owner as a wedding present in the year it was made. And what is true of this piece is true of his art as a whole. Moorcroft’s pots were clearly made for sale, but they were not conceived as (merely) commercial commodities. His enduring ambition was to express in clay his personal response to the world about him, his sense of beauty, and to share it with others. Writing to his daughter on 20 November 1930, he put this into words: ‘ I feel there is a need for interesting, individual things. […] We want pleasant things to live with. Not extreme, not fashionable, but things that will be the outcome of careful thought, things built with the spirit of love in every part of them’. And such objects were not confined to those with the highest monetary value. One hundred years before this record-breaking sale, the Pottery Gazette of September 1925 reported that the then exceptional sum of £100 had been offered for ‘a single piece’ of Moorcroft’s pottery, displayed at the British Empire Exhibition the year before. But this was just half the story of the potter’s appeal, as the critic observed: ‘we are just as much comforted by the thought that even a simple and tolerably inexpensive piece of Moorcroft ware is regarded by thousands of people as a priceless possession’.

That Moorcroft’s work is still highly valued today tells us something about the capacity of his very personal art to reach out across time, but also, more generally, of the continued need for ‘interesting, individual things’. The post-pandemic world of 1930, in the grip of escalating political tension and economic uncertainty, is not without similarities with our own. How fitting, then, that a vase which so powerfully exemplified Moorcroft’s guiding principles at the birth of his new works, should surface, however briefly, in the same week that this same factory, which had long continued to make pottery to the designs of his son, Walter, before passing out of family hands, had been bought by William’s grandson. An encouragement like no other at the start of this new journey to the Dragon’s Gate.

'William Moorcroft, Potter: Individuality by Design' by Jonathan Mallinson is an Open Access title available to read and download for free or to purchase in all available print and ebook formats at the link below.