Margery Spring Rice: Pioneer of Women’s Health in the Early Twentieth Century

As a first-time biographer, I thought a lot during my research about the relationship between the biographer and her/his subject. There must be many issues that other biographers have reflected on before me, but perhaps the one that exercised me most is not so common: my subject, Margery Spring Rice, played a large part in my personal life in my childhood and youth. I am one of her grandchildren, and as a child I had a huge admiration for her, although as I grew up I realised that her high-handedness could also be a cause of embarrassment. She had a fund of stories about her life with which she regaled us, so when I came to write about her there were some pieces of the jigsaw that were very familiar: I knew about her commitment, and that of her family, particularly her aunts Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Millicent Fawcett, to women’s rights, and I had learnt from a very early age that suffragists and suffragettes were not the same. I also knew something about the tragedies that had marked Spring Rice’s personal life: born in 1887, she was of a generation that lost people they loved in both world wars, in her case a husband and a brother in the first, and a son in the second. As I got older, I learnt something too about her colourful love life. I began to understand that the people she encountered tended to fall into two categories, those who adored her and those who loathed her. I recognised that my mother, her daughter, had had a miserable childhood, something that had a huge effect on the way she brought up her own children.

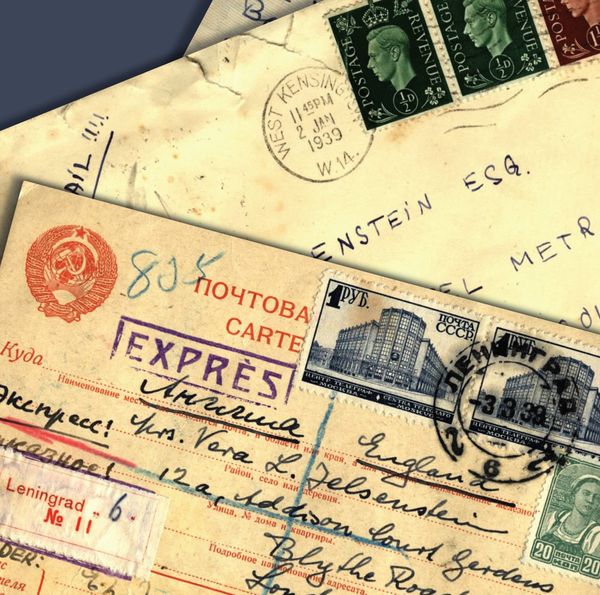

I was lucky enough to find that several members of the family had kept extensive hoards of letters and other papers, so that with the addition of the material in public archives the resources for a biography were not lacking. But as I worked my way through it all, I found myself facing up to Spring Rice’s faults – her selfishness, her inability to enter into the interior world of her children in particular – in a way that I had not quite expected. Though I still loved her dearly, I found myself liking her less. At the same time, I came to enormously admire her public achievements, in particular the founding of, and unstinting thirty-year support for, one of the earliest women’s health and contraceptive clinics in London, the North Kensington Women’s Welfare Centre (not far from where the devastated Grenfell Tower is now). When Spring Rice decided that something needed doing, she would worry at it like a terrier, absolutely refusing to let it go. Had her personal life been smoother or less eventful, I suspect her public life would have been less impressive.

Like every one of us, Spring Rice was a complex character: in my book I aspired to dispassionately convey that complexity at the same time as telling a good story.

Lucy Pollard is the writer of Margery Spring Rice: Pioneer of Women’s Health in the Early Twentieth Century. You can now read & download this title for free here.