On 'William Moorcroft, Potter: Individuality by Design'

by Alex Carabine

“Oh!” I cried at the television. “It’s Moorcroft!”

My husband was suitably perplexed. I had recently been volunteering at Open Book Publishers, and one of my first tasks was proofreading and editing a manuscript entitled William Moorcroft, Potter: Individuality by Design (a pioneering study by Jonathan Mallinson, Emeritus Fellow of Trinity College, Oxford). Now, here we were watching the semi-final of The Great Pottery Throwdown, and for their surprise test the four competing potters were asked to recreate the delicate tube-lining of a famous piece of Moorcroft pottery. The example they were given was exquisite: a design of fruit and flora on a black background, created by designer Emma Bossons. It was called Queen’s Choice, and had been inspired by Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Though the piece displayed on the episode wasn’t original to William Moorcroft, his influences were clear. I felt quite lucky that I had read Mallinson’s gorgeously illustrated book before the episode, so that I could thoroughly understand how Moorcroft’s creative vision continues in the modern designs of his pottery.

Born in 1872, Moorcroft was one of the most celebrated British potters of the twentieth century. He rejected mass production, and considered it his vocation to create an everyday art form that was both functional and decorative, and that would be accessible to as many people as possible rather than made exclusively for the privileged few. ‘If only the people in the world would concentrate upon making all things beautiful,’ he wrote in a letter to his daughter Beatrice in 1930, ‘and if all people concentrated on developing the arts of Peace, what a world it might be.’

His career began in the late stages of the Arts and Crafts Movement of the nineteenth century. This movement was a reaction against the Industrial Revolution, with its emphasis on mass production at the expense of artistry. Eminent Victorians such as the artist William Morris and critic John Ruskin were crucial to the movement, as they drew inspiration from medieval art and romantic folk styles of illustration. Arts and Crafts designs honoured the beauty of nature, and, for the most part, depicted flowers and plants with great attention to detail. The movement went on to influence Art Nouveau, and it was in this cultural moment that Moorcroft emerged as a potter.

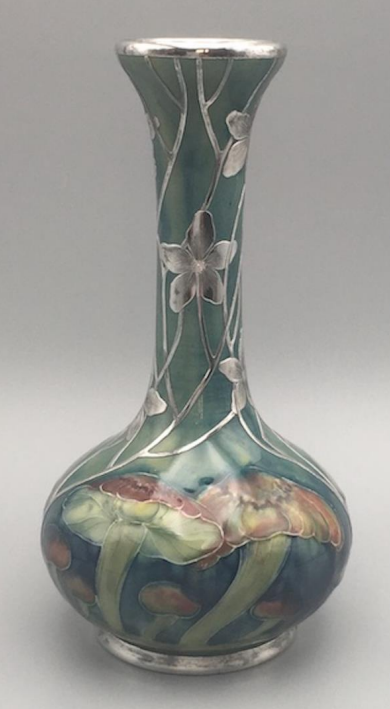

Consider the above image. The taller of the two vases displays an early example of Moorcroft’s tube-lining, which is a skill that involves using a small bottle to squeeze a narrow and delicate line of clay directly onto the surface of the vessel. The design can then be enhanced by painting. It’s a difficult process as the artist needs a steady hand to achieve an even line. The influence of the Arts and Crafts movement is visible in the natural motifs of the vessels – the butterflies and the flowers, for example – while the whiplash lines of Art Nouveau designs are visible in the elongated, flowing forms of the vases.

As time went on, Moorcroft’s craft developed, and with the Toadstool design (see above) he found a new signature style: harmonious colours applied in such a way that they softly bled together, creating an ethereal and delicate effect. Even as the glazes softened, the lines remained clean, and Moorcroft’s pottery became so desirable that he acquired royal patronage, and became Potter to H. M. the Queen in 1928.

Unfortunately, Moorcroft’s career spanned both World Wars, during which time he worked hard to keep his pottery open and his staff employed. During the Second World War, the Government introduced a time of austerity and required potteries to make only domestic items in plain white. Through necessity, Moorcroft had to abandon his beautiful colour palettes and rich decorations. However, the simple elegance of his pottery forms still shone through.

In 1942, he wrote to The Times newspaper: ‘Form exquisitely balanced, pure in tone and texture, is as refreshing as early morning in the country, with the song of the bird… the maker of pottery alone can eliminate the fault in shape that so easily destroys beauty and truth.’ Moorcroft was careful that his domestic items would be functional, carrying enough weight and balance that they would be practical pieces for everyday use. Nevertheless, they each had a stark elegance where the absence of ornament emphasised the purity of line. Even in times of war, Moorcroft’s ware was popular.

William Moorcroft died in 1945, the same year that the Second World War ended. Though he worked hard to establish his pottery and to bring expressive beauty to functional items, he did not live to see his legacy. Despite the fact that he was hugely influential during the first, tumultuous half of the twentieth century, there has been no detailed account of his life. That is, until now. After having read Mallinson’s book and become invested in the life of this remarkable potter, it was with great joy that I saw his work – present in name and spirit, if not in his literal designs – appear on The Great Pottery Throwdown. Moorcroft might not have lived to see his legacy, but Mallinson’s readers will.

“Oh!” I cried at the television. “It’s Moorcroft!” I smiled to see his name, but I was glad to have learned more of the artist.

This is an Open Access title available to read and download for free or to purchase in all available print and ebook formats below.