Stephen Robertson on the Pre-history of the Digital Age

At just around the time I was born, just after the second world war, the first working digital computers were being put together in a handful of laboratories in Britain and the United States. During my lifetime, computers and computing, and more broadly, the information and communication technologies, have pervaded vast areas of our lives.

Should we see that point in history as a revolutionary moment? as a hiatus? Was it the beginning of a fundamental change in human existence? Certainly there is much about the world today that would have seemed like pure fantasy to my parents at the time I was born. The world of email, the internet, online shopping and payment, online management of bank accounts, mobile phones doubling as cameras, digital radio and television, downloaded recorded sound and films, satellite navigation, ebooks, Google, Wikipedia, and social media — all science fiction of the most way-out kind. There is an SF novel by James Blish, written in the late fifties but set in the far future, in which the young protagonist asks a complex question of the City Librarian (a computer). The response sounds like nothing so much as a Wikipedia article.

All those now-familiar elements listed above have been made possible by computers and digital information technologies, and have been brought into existence by means of the same — and this might speak to the idea of a revolution. Nevertheless, such sea-changes do not happen without precursors, and the roots of this particular sea-change go way back. The aim of my book is to unravel this pre-history — all the things we had to learn, to understand, all the ways we had to adapt our thinking, in order to reach this point. Some of these ideas arose during the industrial revolution and the immensely inventive Victorian period that followed it, but many of them go back much further.

The book starts right back at the beginning — the invention of writing. It then follows a number of separate strands of ideas and ways of doing things — not as a linear narrative, but rather in a thematic arrangement. It tries to show how the concept of data has emerged from a multitude of disparate sources to gain an all-pervasive status in the twenty-first century — absorbing along the way numbers, text, images and sounds.

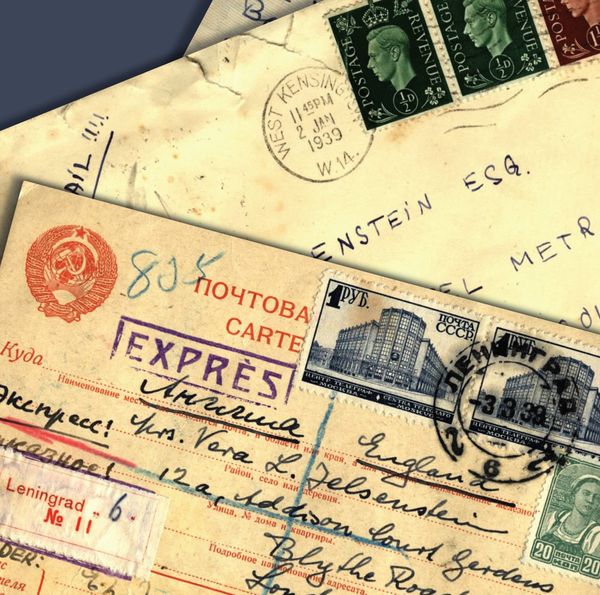

For text, the crucial first step was the invention of the alphabet, around three millennia ago. That was a necessary precursor for many things, including Gutenberg-style printing and, later, the typewriter — and also for developments in writing such as word-spacing and punctuation. The typewriter and its keyboard were central to the process of turning text into data. For numbers, we first had to develop the so-called Arabic numbering system, before we could think about mechanical or electric calculators. But all of this takes place in the context of human communication. Books, libraries, postal systems, pulpits, posters on walls, political rallies — and later, the telegraph and telephone, radio, cinema, television — all these not only preceded but also informed the development of communication systems in my lifetime, including the proliferation of such systems on the web and through the mobile phone network.

The storage, retrieval and transmission of information is central to human communication in all its forms. However, the mechanical processing of information is something else. We see the seeds in ideas about calculators, from the seventeenth century, and in much more ambitious form in the experiments of Charles Babbage in the nineteenth. The first practical machinery emerges at the very end of the nineteenth century, largely due to the work of Herman Hollerith on the US census. A substantial data processing industry arises directly out of Hollerith's ideas in the first half of the twentieth, and then morphs into the computing industry in the second half.

The inclusion of images in the scope of digital communication systems depends not only on the development of photography and the later technology of digitisation, but also on much earlier ideas about how we see the three-dimensional world. We owe a great deal to the Renaissance artists who formulated our idea of perspective, as well as the artists and scientists who got to grips with colour. In the contexts of colour, of 3D images, and of sound, we can think about either the physics of the situation, or the physiology of perception. It was necessary to call upon our understanding of both these domains in order to bring these phenomena into the digital world.

These are the kinds of connections which I seek to bring out in my book.

Stephen Robertson is the author of 'B C, Before Computers: On Information Technology from Writing to the Age of Digital Data'. This is an Open Access title available to read and download for free or to purchase in all available print and ebook formats here.