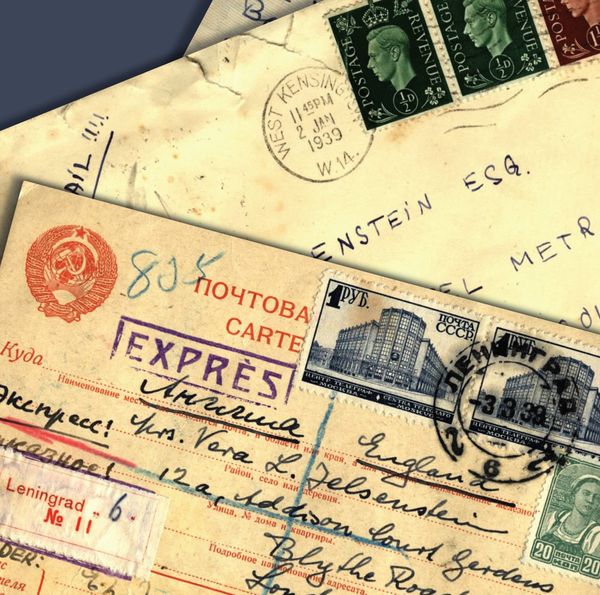

Susan Isaacs: Second Edition

By Philip Graham

This is the Second Edition of a biography first published nearly fifteen years ago. A second edition was required first because of the importance of Susan Isaacs, the relatively neglected subject of the biography and second because twenty-first century research has revealed hitherto unknown material about her.

Susan Isaacs, who lived from 1885 to 1948 was a pioneer in two fields. In the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, she is described as ‘the greatest influence on British education in the twentieth century.’ This is surely enough to establish her as a key figure in British educational history. But, in the mid-1940s, she was also the leading figure in a series of debates in which the two contemporary giants of psychoanalysis, Anna Freud and Melanie Klein confronted each other with bitter mutual hostility. A paper written by Susan Isaacs titled The Nature and Function of Phantasy was the focus of the first two sections of the debate. The record of this debate has been described by an authoritative source as ‘the most important document of the history of psychoanalysis.’

So, it is more than surprising that Susan Isaacs should be virtually an unknown name in the history of British education and psychology. This is only the second biography published since her death seventy-five years ago. Why is it that some pioneers are buried without trace whereas others become, if not household names, at least well-known to those with an interest in contemporary history?

In the case of Susan Isaacs, the reasons for her reputational demise in the field of education are not difficult to detect. Although in the twenty or thirty years after her death in 1948, her books were required reading for those training to be teachers of early years children, shortly after the publication of the 1967 Plowden Report, whose recommendations were significantly based on her work, the idea of child-centred education started to fade in popularity. An avalanche of concern that children left to their own devices were missing out on learning to read and knowing their times table brought it into disrepute. Since that time, there has been, to the disappointment of most teachers, a considerable under-valuation of the importance of play and creative activity in early childhood education.

The story of the rise and fall of the Malting House School directed by Susan Isaacs is instructive in a number of ways. It provides an example of the way in which taking educational ideology to its logical conclusion can both reveal unexpected strengths and abilities in children as well as exposing them to dangers. Further, it is worrying to realise that much educational teaching over a period of some decades in the mid-twentieth century was based on experiences gained in a wildly atypical school in which were placed equally wildly atypical children.

The neglect of Susan Isaacs in the history of psychoanalysis is more difficult to explain but is probably related to the now happily diminishing tendency of psychoanalysts to pay undue respect to their founding forefathers with corresponding dismissal of those who deviated from the true faith. The wide contemporary applications of psychoanalysis and the increasing willingness to evaluate its claims for effectiveness scientifically are welcome signs that these attitudes are changing. These changes may be seen to have begun with Susan Isaacs a hundred years ago, when she drew on psychoanalytic theory to develop a philosophy of education that placed emphasis on providing children with a wide range of learning experiences and helping them and their parents to make sense of their negative, sometimes powerfully negative emotions such as jealousy, hate, anger and despair.

She went on to act as the most popular guide of her generation to countless parents often at a loss to know how to respond to their children’s fears, tantrums and anxieties. Under her pseudonym, Ursula Wise, she was the ‘supernanny’ of her age but with much greater willingness than today’s supernannies to admit to uncertainty and ignorance when it came to explaining why young children behave in the ways they do and to providing techniques to deal with them. Her humility and sympathy with the dilemmas faced by parents might provide a helpful model for today’s self-proclaimed authorities.

This is an Open Access title available to read and download for free or to purchase in all available print and ebook formats below.