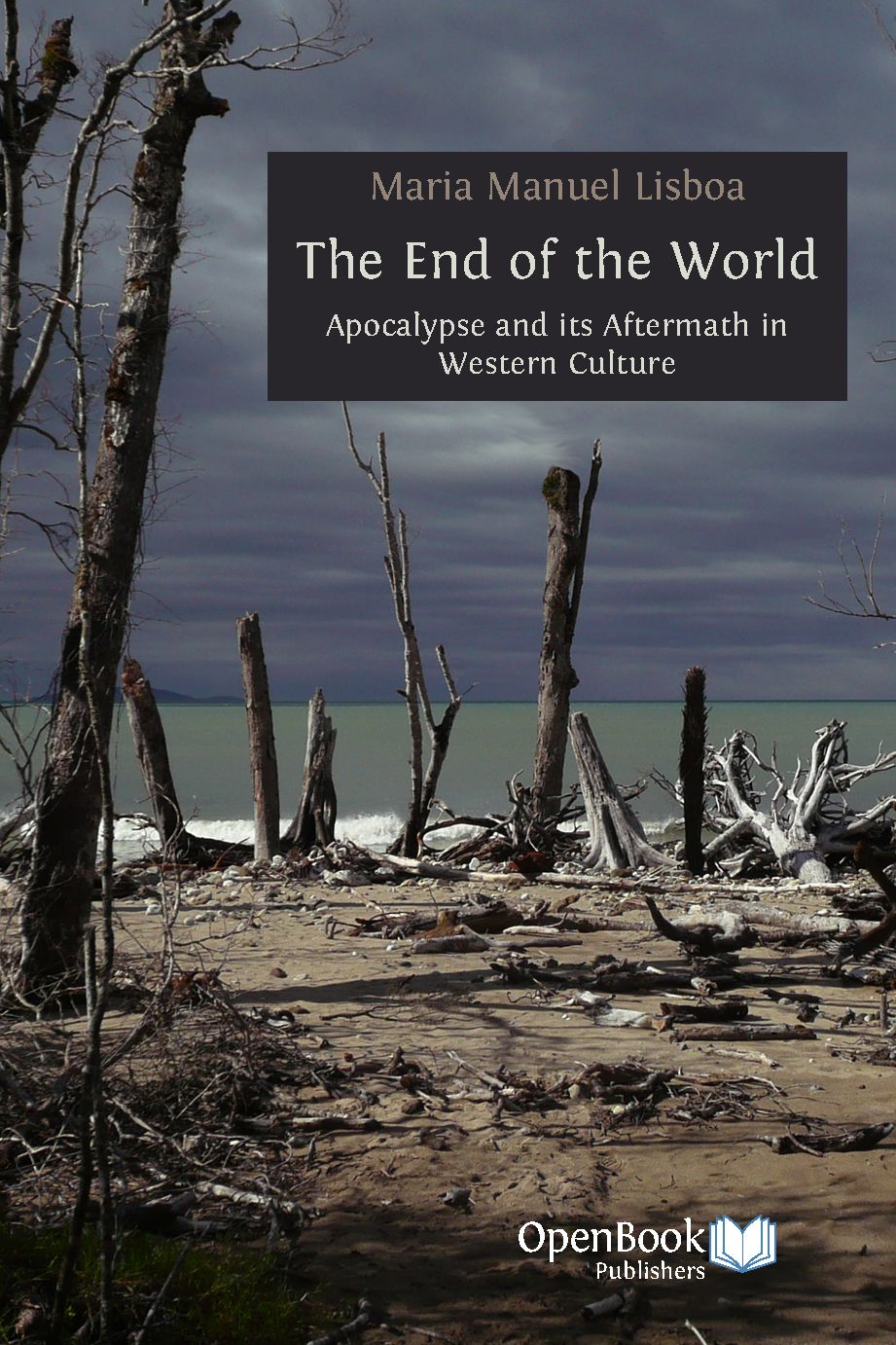

The End of the World: ten years later

By Maria Manuel Lisboa

Who would have thought that a book about the end of the world would feel of such relevance some ten years down the line?

The answer to this question is, who wouldn’t? Fear of widespread calamity has been part of the human psyche ever since whatever the human psyche is came into being, through the tortuous pathways of evolution. And the urge to articulate that fear is at the heart of our most ancient narratives, from the Flood in the Old Testament to the squabble between Aesir and Loki in Ragnarok, to the Kali Yuga in Hindu mysticism. Without that fear, would anyone believe in God? In the beginning we were all atheists.

When I published The End of the World: Apocalypse and its Aftermath in Western Culture in 2011, I looked at the many instances in which literature, art and more recently (comparatively speaking) film have returned to the idea and fear of global annihilation. A bit like repeatedly probing a loose tooth with one’s tongue: it doesn’t help and it hurts a bit, but we can’t help ourselves.

In my book I looked at instances of imagined planetary destruction originating from many causes, from human recklessness to environmental calamity to sheer bad luck. The reassurance to be drawn from the fact that, in the original ancient Greek, the term ‘apocalypse’ signals a necessary clearing of the decks before a new beginning is of the cold comfort variety. In the global wipe-out that supposedly opens the way for a better world, most people die. In a nuclear age, in which the power of science in its negative permutations (weapons of mass destruction, biological warfare, etc.) combines with world travel seen as a both a necessity and an entitlement (where would we be without our professional networking and our regular holidays in the sun?), the conditions for triggering calamity are firmly in place.

There are always, of course, two or more sides to every equation: from the point of view of a travel-averse person, I observe the often unnecessary globe-trotting of academics and the obsession with foreign holidays that now crosses social-class boundaries like nothing else, and I purse my lips sanctimoniously at the self-indulgent burning of fossil fuels, environmental harm and the facilitation of pandemics triggered by unnecessary air travel. On the other hand, with any luck, the more we see of the world and get to know others (or Others), the less inclined we might be to destroy it and them, and instead help out if the need arises.

When Pandora’s box was opened, unleashing havoc upon the world, the only thing left inside it was hope. Long may that thought endure.