The Reinvention of Natural History in Latin American Art

by Joanna Page

Throughout history, visual artists have played a vital role in human efforts to describe, order, and represent the natural world. In Europe, they drew the hybrid, fantastical creatures of mediaeval bestiaries, sculpted rare and precious items for baroque cabinets of curiosities, provided anatomically precise illustrations for eighteenth-century floras, and created life-like scenes with taxidermied animals for natural history museums.

These historical genres give form to ideas about nature that embody mystical, Romantic, Enlightenment, colonial or extractivist values. In recent years, Latin American artists have returned to such genres to rework and recreate them for other purposes. This new corpus is the subject of Decolonial Ecologies: The Reinvention of Natural History in Latin American Art.

In studying these artists’ return to historical modes of representing and classifying nature, I found that their purpose is only partly to develop a critique of their limitations or the ideologies they express. They also seek to rescue some things that could be of value in our own times, which are characterized by accelerating environmental change and a rapid loss of biodiversity.

Contemporary bestiary writers and illustrators in Latin America, including Rafael Toriz and Édgar Cano (Mexico) and Claudio Romo (Chile), resurrect classical and mediaeval monsters and marvels from Europe while inserting others from Amerindian cosmovisions. These hybrid, hyperbolic animals, who constantly intrude in human lives, are unlike the mass-produced, standardized varieties of today’s globalized market, often reared in enclosures that most humans are forbidden to enter. In this context, re-enchanting the natural world through fantastical bestiaries becomes both a critical and a creative act, a defence of diversity and exceptionality, and a celebration of the intimate role that animals used to play in human lives.

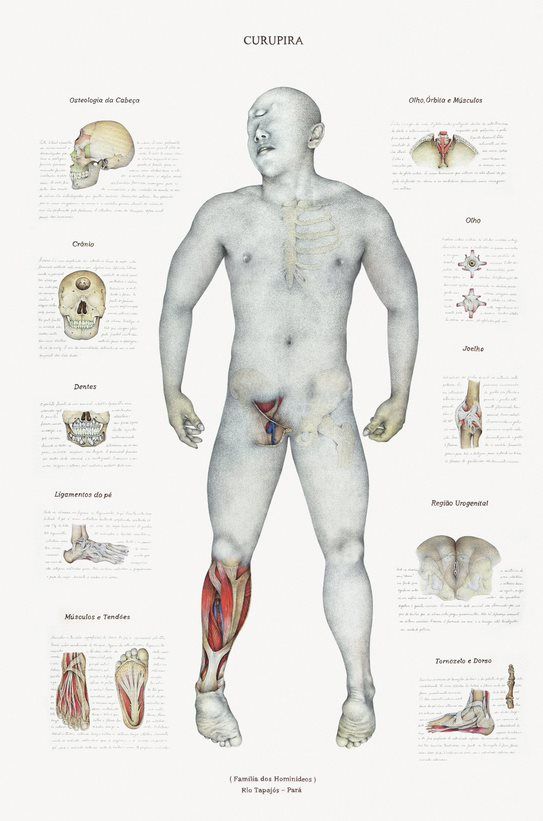

Since Columbus famously spied mermaids near the coast of Hispaniola in 1493, European descriptions of the flora and fauna of the New World have been spiced with marvels and misconceptions of all kinds. In these narratives, Old-World prejudices were projected onto species and environments that lay beyond European knowledge, creating exoticizing images that have endured for centuries. But for artists such as Walmor Corrêa (Brazil), these syntheses of precise observations and mythical tales are also storehouses of imaginaries in which science intermingles creatively with other forms of knowledge that it has since banished to the realm of the non-rational. His anatomical illustrations of the legendary creatures that feature in Jesuit chronicles bring together scientific and popular idioms with a jarring incongruity.

Modern colonial science served the economic needs of Europe by facilitating the development of vast mines and plantations in Latin America. But its impact in the region was not purely economic or environmental. As the Colombian philosopher Santiago Castro-Gómez reminds us, the Enlightenment’s quest to develop a universal scientific language resulted in widespread epistemicide, the systematic erasure of indigenous forms of knowledge.1 This dual legacy of extractivism and epistemicide is the subject of an excoriating critique delivered by Fabiano Kueva (Ecuador) of Humboldt’s universal science. In Kueva’s performances, herbaria exhibitions, and video essays, Humboldt emerges as a central figure in the European exercise of knowledge-by-accumulation. This involved the removal of thousands of specimens, samples, and artefacts from Latin America to Europe, where they were classified and studied, and where most remain in closely guarded museums and depositories.

Enrique Leff, a Mexican economist and environmentalist, calls for a new kind of environmental knowledge that would draw on knowledges and subjectivities that have been marginalized by Western rationalism. This knowledge should not be reduced to the simplifying, objectifying, commodifying approaches to environmental crisis that are commonly found in the natural and social sciences.2 The artists I discuss in the book find multiple ways to expand environmental knowledge in this way. The Herbarium of Artificial Plants (2002-), developed by Alberto Baraya (Colombia), presents a series of botanical plates that initially appear to follow the form of eighteenth-century floras and herbaria, but they feature artificial flowers or plastic reproductions of cacao pods. They also reveal information about the social and cultural uses of plants, together with the colonial politics of their extraction. These details would have been entirely erased from the thousands of illustrations sent back to Europe by artists and naturalists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, who took part in extensive expeditions with the aim of increasing the imperial centre’s knowledge of – and dominion over – the natural riches of Latin America.

Perhaps the most surprising theme that connects this corpus of works is the invitation to rehumanize nature. At a time when we are becoming more aware of the urgent need to establish a relationship with the natural world that is less anthropocentric, many of these works do not call us to limit our impact on other species or to remove ourselves from areas set aside for conservation. Instead, they replace the Western paradigm of conservation with an emphasis on coexistence, collaboration, and co-evolution. Heterogéneas/Criminales (2012), a series of illustrations by Eulalia de Valdenebro (Colombia), denounces the loss of biodiversity and food sovereignty that has resulted from genetic engineering in agribusiness. At the same time, it celebrates the enormous diversity produced by the domestication and selective breeding of plants by indigenous and peasant farmers of the Americas, a process that has developed over thousands of years. The contemporary cabinets of curiosities created by Pablo La Padula (Argentina) expose the historical relationship between European collections, capitalist accumulation and colonial dispossession, but they also defend a new ethic of collecting that brings us into a personal and embodied encounter with the natural world.

Latin American artists are returning to historical methods of classifying and displaying nature with the aim of making knowledge plural. If natural history since the Enlightenment has neutralized the position of the observer, standardized names and universalized systems of measurement, the artists featured in this book place value instead on the contingent, the local, the multiple, the anomalous, the apocryphal, and that which we can only discover through direct, embodied engagement. They do so to re-entwine natural history with human history, rejecting the separation between humans and nonhumans that underpins Western modernity and allowing us to imagine alternative, more reciprocal, ways in which we might co-inhabit with other species in a shared environment.

1 Santiago Castro-Gómez, La hybris del punto cero: Ciencia, raza e Ilustración en la Nueva Granada (1750–1816) (Bogotá: Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, 2010), 18.

2 Enrique Leff, Discursos sustentables (Mexico: Siglo XXI, 2008), 165, 202.

This is an Open Access title available to read and download for free or to purchase in all available print and ebook formats below.