A thank-you note to my publisher and readers

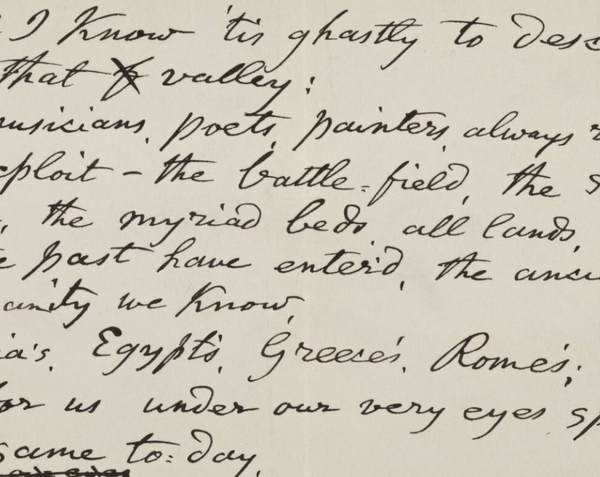

Three days ago, with so much going on—and not going on—in my own country and around the world, a small anniversary slipped by: the one-year mark since Open Book Publishers issued my third book and first open-access title, Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels.

Two months ago, I wrote to OBP Marketing and Library Relations Officer Laura Rodriguez—whose enthusiasm for her titles is benignly contagious—that the book had ‘just blasted past 2,000’. As of this morning, online readership stands at 1,800 and free downloads at 883, for a total of just under 2,700. The three-thousand mark can’t be too far away.

Of course, the spike in ‘sales’ is partly based on tragedy. Tennyson scholars in the US, the UK, and around the world—like me and like millions of other scholars literary and otherwise, academic and independent—are holed up at home waiting for the current plague to pass, hoping it will spare them and their loved ones, hoping—and trying—to get on with their lives.

So the seven-hundred jump in readers of my book over the past two months is at least partly attributable to a lot of folks suddenly having, against their wishes and through no fault of their own, a lot of time on their hands.

Be that as it may, a reader is a reader, and is very welcome. It is heartening that so many scholars and students of literature are, like me, doing their best to put their captivity to good use, to read something new, learn something new, perhaps write something new. We may never become modern-day prisoners of Chillon, learning to love our chains. But our unexpected and unwelcome abundance of free time need not also be unproductive.

After publishing my Tennyson book last year, I turned to the poetry of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, found much of it (to be perfectly frank) forgettable, but fell in love with Aurora Leigh. A half-dozen readings of that verse-novel and related criticism later, I wrote an article-length study of the unidentified and misidentified textual parallels—allusions and echoes—it contains, submitted it to a leading literary journal which sent it out for review, and am now waiting to hear back. All that before the new coronavirus hit.

Since it hit, I’ve returned to the study of Emily Dickinson, who in the 1860s also fell in love with Aurora Leigh, and whose letters, I’ve been finding, are also filled with undocumented textual parallels. Her poetry as well? That remains to be seen, but I wouldn’t be a bit surprised.

One of the miracles of modern technology is, I’ve discovered, how much literary research one can do at home. Without password and without charge, one can access virtually all of pre-twentieth century world literature and criticism, and much of more recent origin.

One can search for words, phrases, lines, and passages in the works of one or more poets, novelists, dramatists and others authors, as well as in scripture, that recognizably recur, for a variety of thematic and other valid reasons, in the works of other, later writers.

One can do meaningful scholarship without having already read everything there is to read and remembered verbatim everything one has read.

Open Book Publishers and other enterprises like it (if any such exist) are also miracles of modern technology, making peer-reviewed, well-edited, well-produced scholarly works widely and immediately available without charge to any and all would-be readers.

By helping scholars and students get through these difficult times and learn something of value along the way, they are performing a valuable public service, deserving and earning the gratitude of authors and readers alike.

R. H. Winnick is the author of Tennyson's Poems: New Textual Parallels. You can read & download this book for free or get your own hard copy here. You can also read Winnick's previous blog post Allusion/Echo and Plagiarism: Walking the Fine Line here and follow him at @rhwinnick.