Our reflections on ‘community over commercialisation’

Since the theme for this year’s Open Access Week is ‘Community over commercialisation’, we thought we would offer some thoughts about how our focus on community, rather than profit, has benefited our press—and some reflections on the potential for community-driven open access (OA) to grow over the next few years.

The practical benefits of a non-commercial and community-focused structure

Open Book Publishers (OBP) is an independent, non-profit, scholar-led OA book publisher. We were founded in 2008 by academics with a clear mission: to make high-quality academic research freely accessible everywhere. In order to serve this mission, OBP was founded as a Community Interest Company (CIC), a regulated non-profit that is obligated to serve a community purpose.

This structure meant that OBP has had a community focus since its beginning—but it was a practical and strategic choice, as well as a principled one. As a CIC, OBP has never had to meet obligations to shareholders on top of its running costs. This has enabled the press to be light and agile, to innovate, and to grow at its own pace.

This was important in the early days of OBP: OA was a new way of publishing that demanded new workflows, business models and infrastructures. Being a non-profit financed by grants and a loan rather than by investment capital gave the founders and directors, Alessandra Tosi and Rupert Gatti, the time to experiment and pilot these while publishing only a very small number of books a year.

It also made it more feasible to resist the Book Processing Charge model of funding, an inequitable approach that requires an author (or funder) to cover the costs and, in some cases, the expected profit margin of a book before publication as a hedge against OA reducing sales. This deeply risk-averse model is common among presses that usually publish closed access, for whom OA is an occasional and unfamiliar mode of publishing—and the fees tend to be higher for presses that are expected to return high dividends to their shareholders (or for those university presses that return a substantial amount of money to their parent institutions every year).

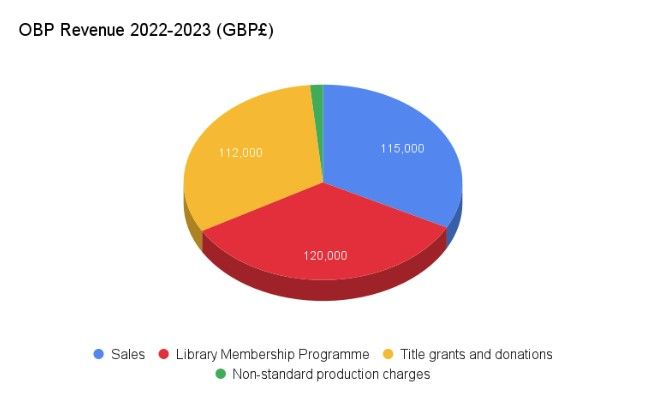

Instead, OBP piloted a Library Membership programme in 2015 to provide an additional income stream, employing a mixed model to fund our costs via income from i) sales of paperback, hardback and EPUB formats, ii) the income from our Library Membership programme, and iii) any grant funding that the author is able to secure. (Publication does not depend on funding, and most of our books are published without it—last year, 35 out of 49 books were published with no additional funding.) The directors began to grow the press by taking on more staff and publishing more books only once this model began to provide sufficient reliable income.

Choosing not to impose fees on authors means we are not limited to only working with those who can afford to pay, thus broadening the communities of scholars we serve. Some have chosen us for precisely this reason—Geoffrey Khan, Regius Professor of Hebrew at University of Cambridge and the series editor of ‘Cambridge Semitic Languages and Cultures’, writes about the importance of not excluding authors from his series in a recent blog post, as well as reflecting powerfully on the extractive relationship closed-access research can have with communities that are studied.

‘Scaling small’: growth through community

Once OBP began to grow, its non-profit status and community focus enabled the directors to set a strategic direction focused on the press’s mission, without the need to pursue higher levels of revenue as an additional responsibility. Currently OBP publishes around 50 books per year and, if the directors chose, we could put all our energies into our own growth and development (as we might if we had a commercial imperative). But instead, Gatti and Tosi decided there was a potentially more exciting and impactful route to be taken by collaborating with like-minded presses, libraries, funders, community organisations and infrastructure providers to build open, non-profit infrastructures and networks that could enable many more presses to publish OA books in an equitable way. This is now a core component of OBP's company ethos, and it is an approach that Copim has described as ‘scaling small’.

This mindset governed our involvement in Copim, an international partnership funded by Arcadia and Research England that, among other developments, has created the Open Book Collective, a community-governed charity currently supporting 13 publisher and service provider members with more than £674k raised from 79 supporting libraries, and which will also award more than £84k in small grants to mission-driven OA initiatives by 2026. Copim has also supported the development of Thoth, a non-profit open metadata management and dissemination service (also a Community Interest Company) that has more than 27 publishers using its platform to manage & disseminate open metadata for OA books (as well as underlying OBP’s own revamped catalogue).

We co-founded ScholarLed, a group of seven independent, academic-led, OA book publishers sharing skills, knowledge and resources to further all of our work, as well as the Open Access Books Network (OABN), a broad and growing community of publishers, librarians, authors and others interested in learning more about, and developing, OA book publishing. Hosting open events, fostering collaborations and sharing free resources, the OABN has also recently been involved in the EU-funded PALOMERA project, exploring why so few OA policies involve books, and what might be done to change this.

As well as contributing to these communities, we are supported by them. Infrastructures built by Copim are part of our workflows; collaborations fostered by ScholarLed and the OABN inform and improve what we do. Essential funding flows from our Library Members, whose substantial contribution is so necessary to our work, and our advisory and editorial boards offer invaluable advice and expertise as we look to innovate and grow our impact in different ways. Some readers choose to donate to us in support of our approach. Finally, our community of authors trust us with their work, the foundation of any publisher’s activity, and in return we do all we can to share that work as widely as we can, in the best form possible.

It's also worth noting that several of these larger ongoing initiatives were first sparked by small grants. The Polonsky foundation funded OBP to develop an open source metadata database and website, which was a crucial seed for the idea that became Thoth. And an OpenAIRE grant brought together the presses that founded ScholarLed (itself a subset of the Radical Open Access Collective) which went on to devise the initial bid for Copim. These early, small grants brought like-minded people and organisations together and facilitated deeper collaboration and opportunities for development—so by enabling collaboration, these smaller grants made space for alternatives to commercialisation.

A growing role for communities in OA publishing?

Open Access Week offers a moment to reflect on developments in OA, and, given our investment in community ways of working, we are particularly interested to see the founding and development of other communities of practice based around OA. These include the Open Institutional Publishing Association (a UK network), as well as the New University Presses in the Netherlands, the Irish Open Access Publishers. (There is also the recently-announced University-Based Publishing Futures group in North America, which we're keen to learn more about). These organisations are invested in growing equitable and resilient OA publishing via mutual support and collaboration rather than competition, which is a spirit we recognise from our work with Copim and other communities. It is an approach that is developing fast.

A focus on community is also being driven by the increased profile of Diamond OA, with the DIAMAS project in Europe, the UNESCO Global Diamond Open Access Alliance, and the Global Summit on Diamond Open Access helping to drive debates about whether Diamond is ‘just’ a model (free to read and free to publish) or whether it also requires community ownership and/or control over the publishing outlets themselves. Understanding what that control might look like requires a firm focus on governance, a topic that is currently not receiving the serious attention it deserves in conversations about OA.

The increased emphasis on community has not gone unnoticed in commercial circles either, and casual claims of being ‘community-driven’ are cropping up more often. We would encourage caution when hearing these warm words—what do they mean in practice? Can they be backed up by robust governance models, or by evidence of tangible investment in the communities in question, or are they simply a marketing label designed to part libraries and funders from their cash?

It will be fascinating to see where these currents have taken us when we arrive at next year’s Open Access Week.