Tackling Simplified Sign System Handshapes: Five Basics to Get You Started

by Tracy T. Dooley

Signing can seem like a daunting task for hearing people who have never before tried to communicate using a sign language. The full and genuine sign languages of Deaf persons that are used around the world have their own distinct handshapes, vocabularies, grammars, and rules for usage within their societies. Studying one or more of the natural sign languages of Deaf persons can provide a fascinating look into the many fruitful and creative means of expression used by people from diverse sociocultural perspectives and life experiences.

My academic mentor, colleague, and beloved friend, John Bonvillian, spent his life dedicated to learning more about the sign languages of Deaf people and the ways in which manually produced signs could benefit the many individuals who struggle to communicate verbally and/or exist within a world dominated by speech. When John heard Gail Mayfield’s heartfelt entreaty to create a sign-communication system comprised of signs that would be easier to learn and form, he enthusiastically dedicated himself to that task with a joyful heart (see his brother William’s blogpost on The Possibility of Signs).

John’s linguistic research with Ted Siedlecki, Jr. in the 1990s regarding the formational parameters of American Sign Language (ASL) signs and how they are learned by the typically developing hearing and deaf children of Deaf parents (see Simplified Signs, Volume 1, Chapter 3) provided a sound foundation for the development of a sign system comprised mostly of easier-to-form handshapes. Their analysis found that forming correct handshapes was the most difficult task for young signing children to master. This was because the children’s ability to produce the more complex handshapes often present in Deaf sign languages frequently lagged behind the children’s ability to control the fine motor skills of their hands necessary to produce such complex handshapes.

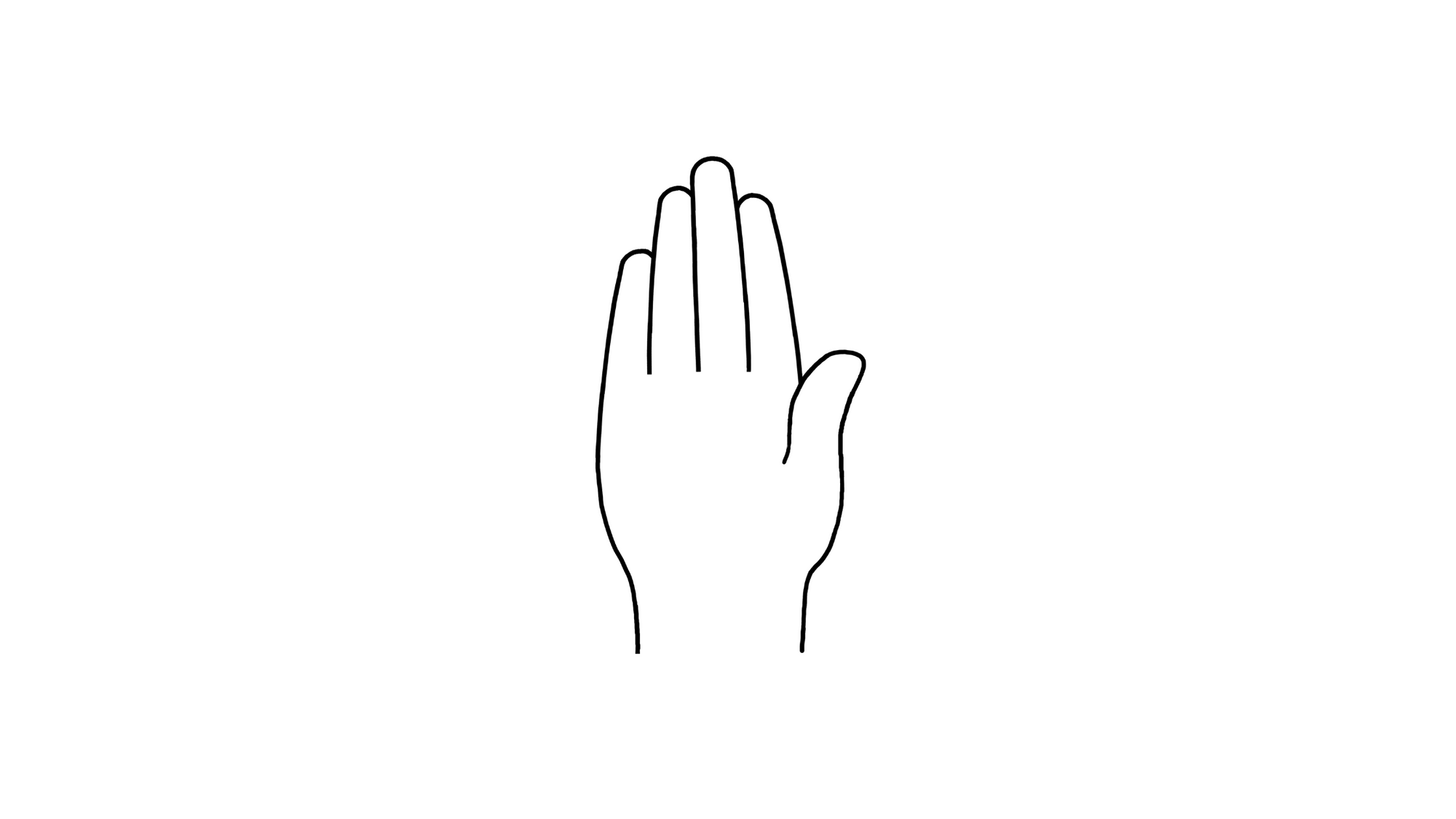

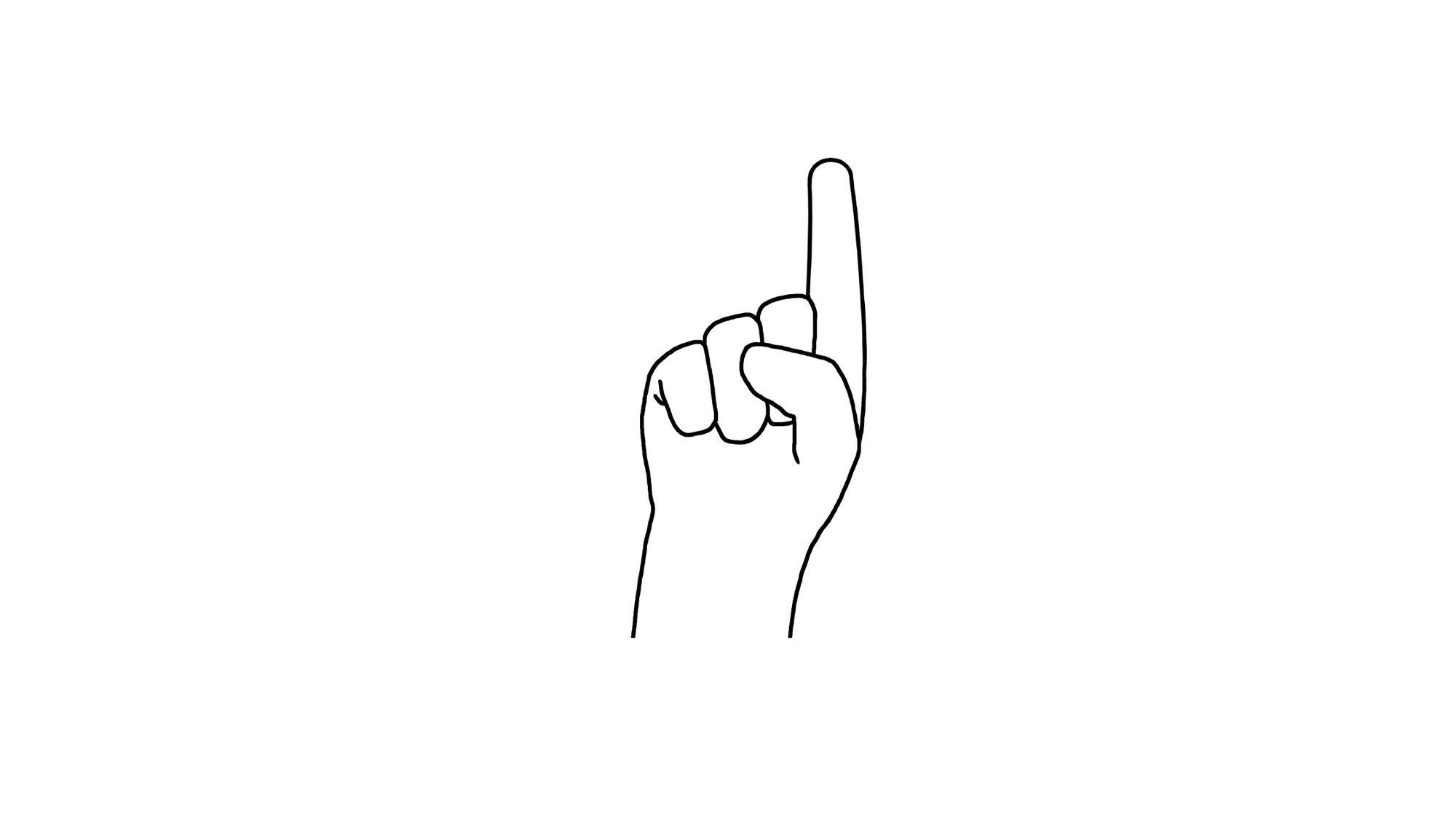

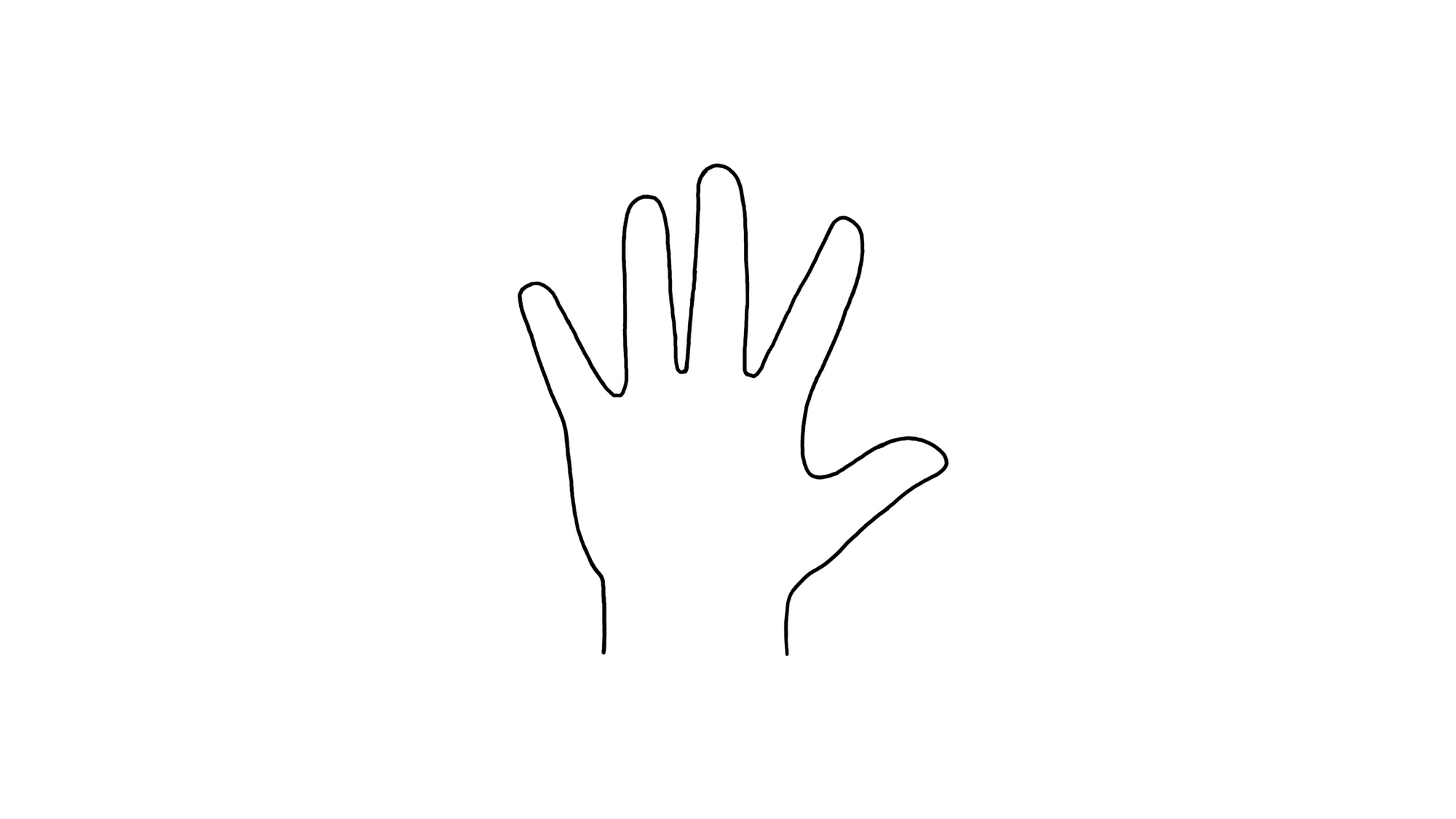

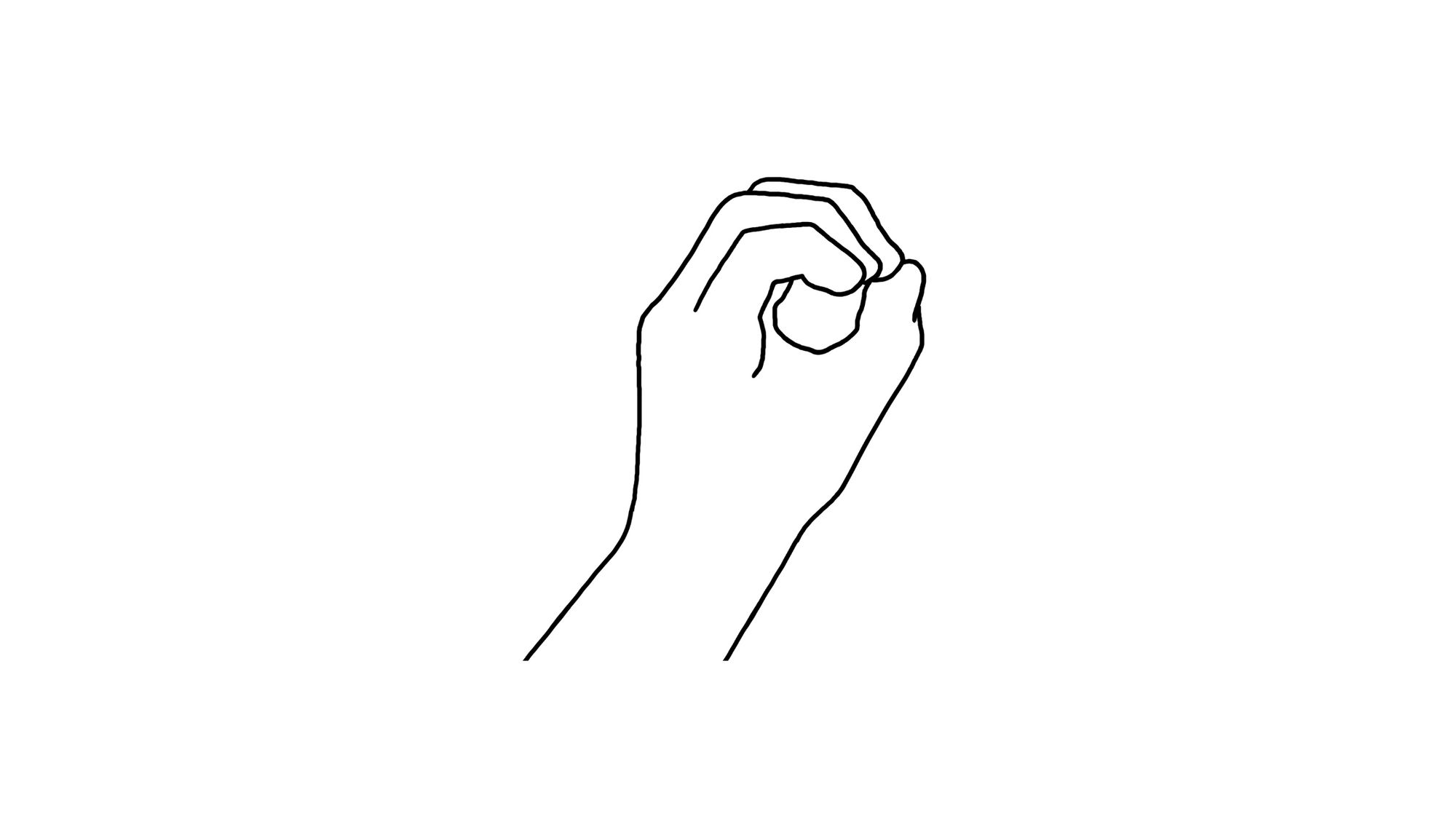

Since many non-speaking or minimally verbal individuals may also have difficulties with fine motor control, particularly with the oromotor skills necessary for fluent speech and the manual motor skills necessary to produce recognizable signs, it is vital that signs used by such persons be relatively easy to form. In addition to noting the specific ASL handshapes that were more difficult to form by young signing children, Bonvillian and Siedlecki’s investigations found that certain handshapes were produced easily and accurately from a relatively young age. These handshapes included such basic handshapes as the flat-hand, the pointing-hand, the fist, and the spread- or 5-hand.

Not surprisingly, then, a preliminary analysis that I performed in 2015 of the handshapes used in the Simplified Sign System (SSS) showed that these four handshapes, along with the tapered- or O-hand, were the most prevalent handshapes in the first 1000 signs of the system. The flat-hand alone accounts for nearly 26% of the handshape usage. The pointing-hand, fist, and spread- or 5-hand account for roughly another 38.5%, and the tapered- or O-hand for 6.50%. These five handshapes together make up nearly 71% of all of the handshape usage in the initial lexicon. Thus, the majority of the signs available in Simplified Signs, Volume 2, Chapter 11 should be highly accessible to persons experiencing temporary or chronic difficulties with their motor skills.

In keeping with the ethos of universal design (see Simplified Signs, Volume 1, Preface and Acknowledgments), in which the development of a product, service, or environment takes into account the needs of people with a range of abilities, the Simplified Sign System should also be easy to use not only by non-speaking persons with motor impairments, but also by their family members, friends, work colleagues, and people in their communities. Indeed, we all benefit from such things as elevators, ramps, and other modifications to our environments, even if we forget the origins of these inventions in civil rights movements. In fact, one can argue that it is the presence of persons with various abilities and disabilities that helps to drive innovation, technological advancement, and positive societal changes that benefit everyone.

Plus, signing is not as daunting a task as you might think. In fact, accompanying our speech with manual gestures, facial expressions, and other bodily movements is something that many people do on a regular basis. Furthermore, such incorporation of communicative gestures with speech may be so prevalent that we do it without even thinking about it or being consciously aware of it. Try this fun experiment with someone you know and trust: when in the middle of a typical conversation with that person, stop moving your body, your arms, your hands, and your head. Also, stop using facial expressions—no eyebrow raises, no pursed lips, no smiles, no frowns, no rolls of the eyes, no gazing at anything or anyone except the person with whom you’re talking—and see how long you can keep it up. If the two of you aren’t laughing within minutes (or even seconds) of the switch, then you have truly overlooked the many ways in which our bodies and the parts of our bodies speak for us. Indeed, it can be extremely difficult to NOT use some form of communicative gesturing when speaking with others, especially with people you do not know.

As a result, many of you out there already have the basics of gestural communication in your skill set, even if you’re not consciously aware of it. So, do yourself a favor—let go of your fears, flex your fingers, and try to produce the following five most frequently used handshapes in the Simplified Sign System. If you don’t do it “right” the first time, try again! There’s no judgment here and no deadlines to meet. There is, however, quite a bit of room for laughter, fun, and the joy and satisfaction that come from learning to communicate with your hands.

Illustrations by Val Nelson-Metlay.

This book is now available to read and download for free. Please, click here to access Vol. 1 and here for Vol.2.

We will be hosting an Online Book Launch for this title on the 3rd September 2020 at 4 p.m. BST/ 11 a.m. EST. You can RSVP here.